When does GenAI add the most value? Where do we need human creativity in our work? James Woodman considers the benefits of predictability – and the power of making that a conscious choice.

We say “artificial intelligence” without thinking. But the intelligence you see isn’t artificial – and it isn’t the machine’s.

What AI really delivers is predictability. That can be powerful – or just average.

This perspective is not anti-AI. There are enormous opportunities to do exciting new things. But the more I talk to people about GenAI, the more I realise we’re at risk of misunderstanding what it actually does. I think the name itself is a misdirection, and it’s nudging us towards underestimating the importance of humans.

So here’s my case for why GenAI isn’t quite what we think it is – and why that matters.

Any ‘intelligence’ that we see in AI is not artificial. It’s the opposite. It’s entirely human.

It comes from the humans who design and program the AI models.

It comes from the humans who create every bit of original content that the AI models are trained on.

And it comes from the human prompting the AI tool to create something new.

None of that intelligence came from a computer. None of it is artificial. But everyone I meet – me included – uses the term ‘AI’ to suggest that the machine brings its own thinking to the conversation. It doesn’t.

What the computer really brings is its ability to predict what happens next.

You probably know that behind the scenes, GenAI models are all about statistics and probability. Given a particular set of words in a particular context, what word is likely to come next? Computers are good at that.

And I think that’s what makes generative AI’s output so convincing. It’s statistically likely. It’s probable.

The ability to judge whether one thing follows another (or not) is part of what makes us human. Without pattern recognition, we wouldn’t survive: it’s how our brains make sense of a complex world. Even if you love surprises, you still expect life to be mostly predictable. We want things to fit.

But I think there’s a fundamental difference between the ‘fit’ of something created by a human, and the ‘fit’ of something generated by AI.

The GenAI ‘fit’ isn’t because it’s intelligent, but because it’s mathematically likely. It’s literally calculated to produce patterns that our brains find appealing and coherent. And so we’re quick to accept the impression that there’s something similar to human thought taking place.

I find it more helpful to think of GenAI as ‘Simulated Intelligence’.

The simulation is brilliantly convincing, and it can be incredibly useful. But it’s not intelligent. That mathematical process is creating a kind of ‘average’ of all the patterns it’s seen in its training data.

Think about what that kind of ‘average’ looks like in the workplace.

The average meeting. The average email. The average policy. The average mandatory training.

That’s what GenAI is creating.

Technically, that ‘average’ is closer to the mode than the mean – it’s smoothing outliers and amplifying patterns closest to the centre.

And there’s nothing inherently good or bad about that – but I think it’s vital that we consciously pay attention to what’s happening.

So the question I think we should ask is: Do I want predictability here?

Sometimes the answer is “yes, absolutely”. ‘Average’ doesn’t mean ‘mediocre’.

You’re creating a chatbot to answer questions about the company’s regulatory environment. Do you want it to be predictable? Yes. Ideally you want 100% predictability, although I’m not convinced anyone doing this with AI can guarantee that yet.

You’re bringing in a coach to support people on your team. Do you want that coach to ask predictably open, supportive questions? Yes. And an AI coach can do that to a consistently high standard. It’s a great example of what these tools can do when thoughtfully designed. It’s different to working with a human – but there’s growing evidence that it has a positive impact.

You’re signing up with a foreign language tutor. Do you want them to predictably get words and grammar right? Do you want them to predictably keep the focus on your weakest areas? Yes. That’s why people subscribe to services like Duolingo.

But do we always want that? No. Sometimes predictability is actively unhelpful.

Do you want your company to settle for a predictable, average marketing slogan?

Do you want to hire someone who sends you a predictable, average job application?

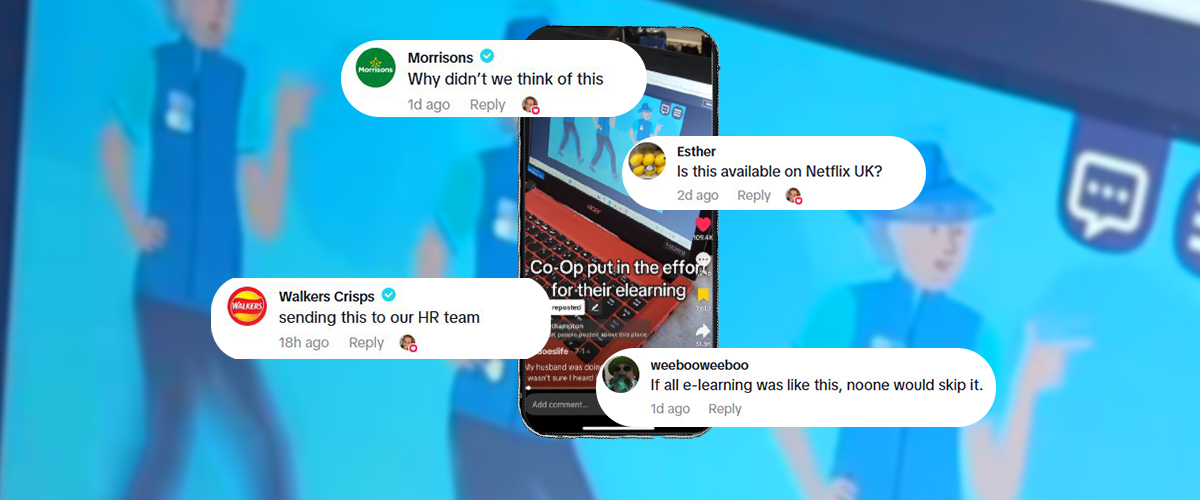

Do you want to spend time on a predictable, average piece of e-learning?

For me, the answer to all those questions is a powerful no.

If you want people to act differently, if you want to promote change – don’t be predictable.

Make safety training so memorable, people are still talking about it on TikTok five years later.

Put Stefan’s baby in charge of cybersecurity.

Hire a pink-haired puppet to represent your employees’ conscience.

Break the pattern. Be unpredictable.

We don’t necessarily get to decide how ‘average’ our lives are going to be. But we have total control over which parts of our thinking to delegate to GenAI.

I said earlier that there’s nothing inherently good or bad about predictability. Doctors and lawyers are trained to be predictable and correct.

And GenAI is a powerful tool. It makes it easier than ever for anyone to produce something ‘average’ – in an infinite number of areas.

So be consciously average. Make it a choice. Ask yourself: do I want predictability here?

Remember, the language models of the future are being trained on AI-generated content.

That means their output is going to get more consistently ‘average’ and predictable over time.

Follow that trend into the future, and – unless more of us choose to make our GenAI use conscious, creative, and critical – we risk a world that converges on the most average PowerPoint presentation ever made.

So I’m writing this to remind myself that I want to keep asking that simple question before I use GenAI.

Whatever I’m about to do, do I want predictability? I have a choice.